Photography may not have a history as long as painting- but the art form certainly has a vibrant past. As such, there are a large variety of different types of photography throughout time, with most classic niches revolving around prints! Photography used to be a purely physical medium, versus its digital format now. One such incredible facet of the craft is photogravure, also known as gravure photography.

Gravure photography came from the 1820s and can still be found today! This style is regarded for its beautiful print making and deep contrasts, creating one of a kind art pieces to last a lifetime. Here is our full article on everything you want to know about gravure photography!

What is Photogravure?

In simple terms, photogravure is an intaglio printmaking process where a copper plate is grained and then coated with a light-sensitive gelatin tissue which had been exposed to a film positive, and then etched, resulting in a high quality intaglio plate that can reproduce detailed continuous tones of a photograph. This is a fancy way of saying that gravure photographs are those etched into copper and printed traditionally with ink.

Intaglio refers to printing and printmaking techniques in which the image is incised into a surface and the incised line or sunken area holds the ink. These processes produce a wide variety of tones, something that is deeply sought after with printmaking photographers.

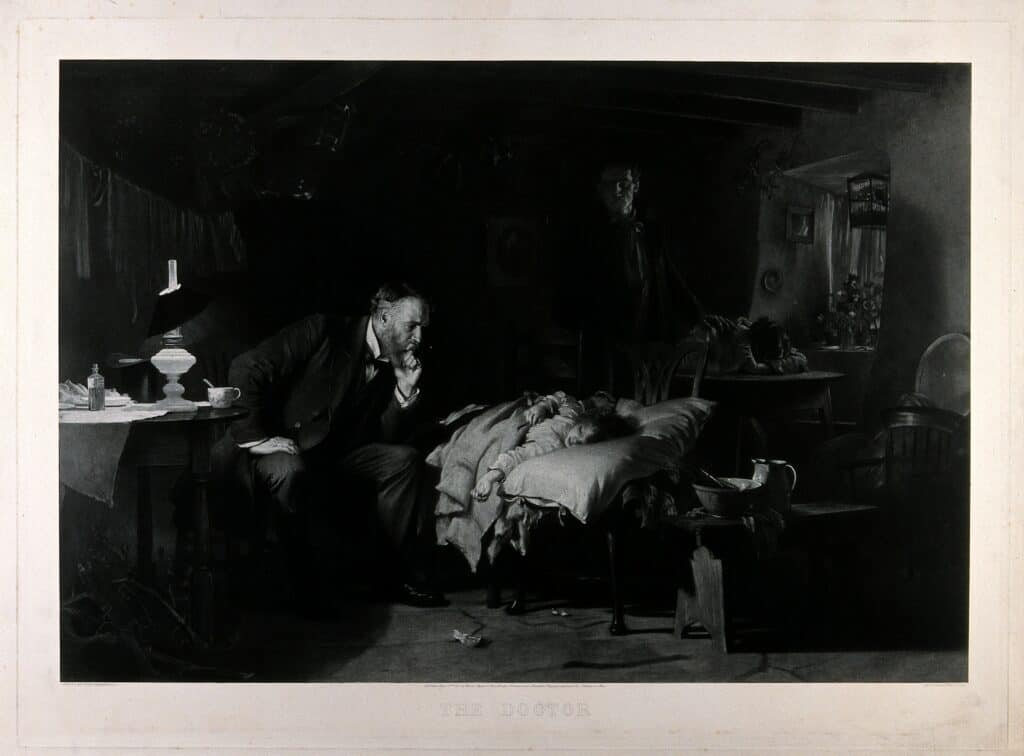

As the prints are black and white, ensuring that the qualities of black and white images continue forth is necessary. The most important is that of tone, which is the overall lightness or darkness of an image. Darkness tends to make images moody while lightness makes images more optimistic. How you use tone affects a viewer’s perception of an image.

Photogravures result in images that appear to have a velvety matte surface, filled with deep shadows, delicate half tones, and luminous highlights. All of which showcase the absolute best in photographs lacking color, allowing them to compete.

The History and Its Place in the Modern World

Photogravure has an eclectic history, and although it was eventually replaced with more practical techniques, you can still find gravure photography today.

We must go back in time to the early-nineteenth century. This century marks a fascinating point in human history, revolving heavily around science and the arts, with etchings and engravings gaining a tremendous amount of popularity as a way to illustrate books. As such, it was only natural for a process such as photogravure to come about.

A scientist and inventor by the name of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce had his interest piqued by lithography, which is the process of printing from a flat surface treated so as to repel the ink except where it is required for printing. Due to a medical condition, he was inspired to explore methods using light itself as his ‘etcher’. Thus the art of photography was born.

In France, Louis Daguerre was also inventing photography. The two inventors had been introduced and began working on the same common goal. In 1839, the Daguerreotype was announced, which was a method of printing by engravers who copied images using traditional methods of engraving.

Efforts to etch daguerreotypes ended when William Henry Fox Talbot invented a paper-based negative/positive process, which is a printing process we even use today. This quickly killed off the Daguerreotype. Talbot’s calotype negatives yielded hundreds of identical prints that could be mounted or tipped-in to albums and printed books. Unfortunately, these images were not permanent and quickly faded, which led Talbot to have to find another way. This was the birth of the photogravure. Talbot improved many aspects of the process over the course of years, including the base, etchant, and resist used, and because his focus was on accurately reproducing tone (an important part of black and white photography). Talbot worked on his photogravure process up until his death in 1877.

“In 1879, Karl Klíc, a painter living in Vienna, patented an improvement on Talbot’s process that allowed for deeper etched shadows. In addition, Klíc invented a technique of transferring the negative image to a copper plate by way of gelatin-coated carbon paper. The superior results yielded the official Talbot-Klíc photogravure process.” With photography being argued to be a fine art at around the same time by a man named Peter Henry Emerson, photogravures became a known method of photography.

Emerson proved his point of photography being an artform when his photogravures illustrated five books between 1887 and 1895. In more modern times, photography became accessible to the masses. Photographers that proceeded to be inspired by Emerson work began to further explore photogravure resulting in the first truly international photographic movement.

Today, although modern printing techniques have a bit of a monopoly over the industry, there is still a place for photogravure. The process was rediscovered in the 1970s, when the painstaking physical aspect of creating fine art photography became popularized. Gallerist William Thomas is quoted as saying “Through the photogravure shines a dedication to craft and truth – and something more, something ineffable and profound – a stillness, a sense of dignity and place in prints still with us, but fading fast from today’s instant-gratification, throw-away culture that celebrates superfluous surface glitz and visual promiscuity as a kind of random, “drive-by” art.”

How Does One Do a Photogravure?

Now comes the million dollar question: how exactly does one create a gravure photograph?

Really, it’s creating the copper plate. That takes a few skilled steps to complete:

Firstly, you must have a photograph already as a film negative. You then create a continuous tone film positive from the negative.

Next, you need to sensitize a sheet of pigmented gelatin tissue by immersion into a 3.5% solution of potassium dichromate for 3 minutes. Once dried against an acrylic surface, it is ready for the next step.

After waiting approximately a day, the third stage is to expose the film positive to the sensitized gravure tissue. The positive is placed on top of the sensitized sheet of pigmented gelatin tissue. The sandwich is then exposed to ultraviolet light. A separate exposure to a very fine stochastic or hard-dot mezzotint screen is made, or alternatively an grain of asphaltum or rosin is applied and fused to the copperplate (usually before the exposed gelatin tissue is adhered to the plate).

Next, you have to adhere the exposed tissue to the copper plate. The gelatin tissue is placed down onto the highly polished copper plate under a layer of cool water. It is squeezed into place and the excess water is wiped clear.

Once adhered, use a hot water bath to remove the paper backing and to wash away the unexposed gelatin. The remaining depth of hardened gelatin is relative to the exposure.

Now the fun part: You must etch the plate in a chloride bath. The ferric chloride migrates through the gelatin, etching the shadows and blacks under the thinnest areas first. The image is etched onto the copperplate, creating a gravure plate with tiny “wells” of varying depth to hold ink.

You then have a finished plate, and use it to make prints with ink.

In conclusion, photogravure is one such photography niche that helped the artform become recognized as a true art in the first place! You can tap into photography’s history by trying a photogravure of your own.